From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For the philosophy journal, see

Noûs.

Nous (British:  /ˈnaʊs/;[1] US: /ˈnuːs/), also called intellect or intelligence, is a philosophical term for the faculty of the human mind which is described in classical philosophy as necessary for understanding what is true or real, very close in meaning to intuition. It is also often described as a form of perception which works within the mind ("the mind's eye"), rather than only through the physical senses.[2] The three commonly used philosophical terms are from Greek, νοῦς or νόος, and Latin intellectus and intelligentia respectively.

/ˈnaʊs/;[1] US: /ˈnuːs/), also called intellect or intelligence, is a philosophical term for the faculty of the human mind which is described in classical philosophy as necessary for understanding what is true or real, very close in meaning to intuition. It is also often described as a form of perception which works within the mind ("the mind's eye"), rather than only through the physical senses.[2] The three commonly used philosophical terms are from Greek, νοῦς or νόος, and Latin intellectus and intelligentia respectively.

In philosophy, common English translations include "understanding" and "mind"; or sometimes "reason" and "thought".[3][4] To describe the activity of this faculty, apart from verbs based on "understanding", the verb "intellection" is sometimes used in philosophical contexts, and the Greek words noēsis and noein are sometimes also used. In colloquial British English, nous denotes "common sense", which is close to its original everyday meaning in Ancient Greece.

Apart from referring to a faculty of the human mind, this philosophical concept has often been extended to describe the source of order in nature itself.

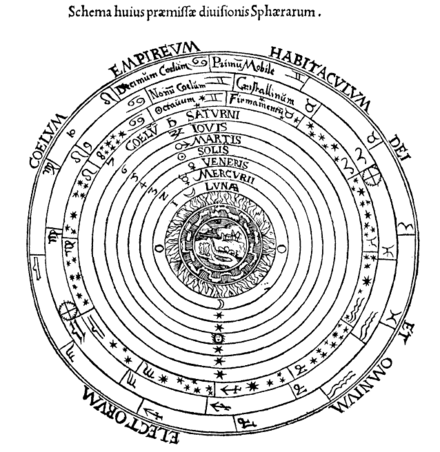

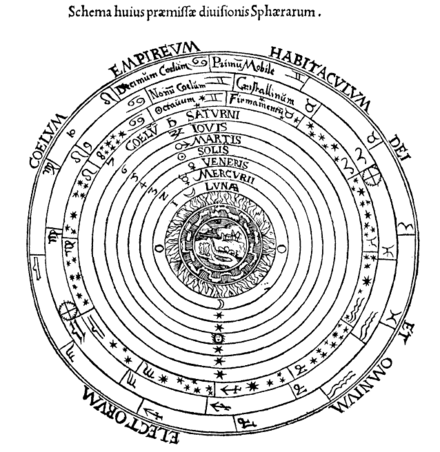

This diagram shows the medieval understanding of

spheres of the

cosmos, derived from

Aristotle, and as per the standard explanation by

Ptolemy. It came to be understood that at least the outermost sphere (marked "

Primũ Mobile") has its own intellect, intelligence or

nous - a cosmic equivalent to the human mind.

[edit] Introduction: nous in philosophy

The basic meaning of "nous" or "intellect" is "understanding", but several sources of types of "understandings" are often distinguished from each other:

- Sense perception is a source of raw information about things, but it needs to be interpreted in order for there to be converted into real understanding.

- Reason is a source of new understandings but it is built by putting together and distinguishing other things already understood.

Philosophical discussion of nous has therefore centred around the origin of the most basic understandings which allow people to make sense of what they see, hear, taste or feel, and which also allow them to start reasoning. These basic understandings are often felt to at least include such things as understandings of geometrical and logical basics, and also an ability to generalize properly into correct categories or universals, setting definitions. This mental step between perception and reasoning has sometimes been discussed as an aspect of perception or an aspect of reasoning, as will be seen below.

The question then also arose of whether there can really be any source of such basic understanding other than the accumulation of perceptions. Somehow the human mind sets definitions in a consistent way, because people perceive the same things and can discuss them. So the argument goes, as will be shown below, that people must be born with some innate potential to understand the same things the same ways. And in addition to this it has also been argued that this possibility must require help of a spiritual and divine type. The question of where understanding comes from, is therefore related to the question of what knowledge is, and how things can and should be defined or classified.

Another important philosophical discussion concerning nous stemming from these, involves not only human thinking, but the nature of the cosmos itself. As mentioned above, some philosophers proposed that the human mind must have an ability to understand which is divine, and independent of normal sense experience and physics. This ordering of the individual human mind, it is then argued, must be somehow derived from a cosmic mind which orders nature just like the human mind orders its understanding of nature. This was claimed from an early time, by Greek philosophers such as Anaxagoras. By this type of account, it came to be argued that the human understanding (nous) somehow stems from this cosmic nous, which is however not just a recipient of order, but a creator of it. Such explanations were influential in the development of medieval accounts of God, the immortality of the soul, and even the motions of the stars, in Europe, North Africa and the Middle East, amongst both eclectic philosophers and authors representing all the major faiths of their times.

[edit] Pre-Socratic usage

The first use of the word

nous in the

Iliad.

Agamemnon says to

Achilles: "Do not thus, mighty though you are, godlike Achilles, seek to deceive me with your wit (

nous); for you will not get by me nor persuade me."

[5]In early Greek uses, Homer for example used nous to signify mental activities of both mortals and immortals, for example what they really have on their mind as opposed to what they say aloud. It was one of several words related to thought, thinking, and perceiving with the mind. Amongst pre-Socratic philosophers it became increasingly distinguished as a source of knowledge and reasoning and opposed to mere sense perception, or thinking influenced by the body such as emotion. For example Heraclitus complained that "much learning does not teach nous".[6]

Among some Greek authors a faculty of intelligence, a "higher mind", came to be considered to be a property of the cosmos as a whole.

The work Parmenides of Elea set the scene for Greek philosophy to come and the concept of nous was central to his radical proposals. He claimed that reality as the senses perceive it is not a world of truth at all, because sense perception is so unreliable, and what is perceived is so uncertain and changeable. Instead he argued for a dualism wherein nous and related words (the verb for thinking which describes its mental perceiving activity, noein, and the un-changing and eternal objects of this perception noēta) describe a form of perception which is not physical, but intellectual only, distinct from sense perception and the objects of sense perception. These eternal immaterial objects which people perceive in their mind are the equivalent of the forms or ideas, in the later philosophy of Plato and Aristotle.

Anaxagoras of Clazomenae, born about 500 BC, is the first person who is definitely known to have explained the concept of a nous (mind), which arranged all other things in the cosmos in their proper order, started them in a rotating motion, and continuing to control them to some extent, having an especially strong connection with living things. (However Aristotle reports an earlier philosopher from Clezomenae named of Hermotimus who had taken a similar position.[7]) Amongst Pre-Socratic philosophers before Anaxagoras, other philosophers had proposed a similar ordering human-like principle causing life and the rotation of the heavens. For example Empedocles, like Hesiod much earlier, described cosmic order and living things as caused by a cosmic version of love,[8] and Pythagoras and Heraclitus, attributed the cosmos with "reason" (logos).[9]

According to Anaxagoras the cosmos is made of infinitely divisible matter, every bit of which can inherently become anything, except Mind (nous), which is also matter, but which can only be found separated from this general mixture, or else mixed in to living things, or in other words in the Greek terminology of the time, things with a soul (psuchē).[10] Anaxagoras wrote:

All other things partake in a portion of everything, while

nous is infinite and self-ruled, and is mixed with nothing, but is alone, itself by itself. For if it were not by itself, but were mixed with anything else, it would partake in all things if it were mixed with any; for in everything there is a portion of everything, as has been said by me in what goes before, and the things mixed with it would hinder it, so that it would have power over nothing in the same way that it has now being alone by itself. For it is the thinnest of all things and the purest, and it has all knowledge about everything and the greatest strength; and

nous has power over all things, both greater and smaller, that have soul [

psuchē].

[11]

Concerning cosmology, Anaxagoras, like some Greek philosophers already before him, believed the cosmos was revolving, and had formed into its visible order as a result of such revolving causing a separating and mixing of different types of elements. Nous, in his system, originally caused this revolving motion to start, but it does not necessarily continue to play a role once the mechanical motion has started. His description was in other words (shockingly for the time) corporeal or mechanical, with the moon made of earth, the sun and stars made of red hot metal (beliefs Socrates was later accused of holding during his trial) and nous itself being a physical fine type of matter which also gathered and concentrated with the development of the cosmos. This nous (mind) is not incorporeal; it is the thinnest of all things. The distinction between nous and other things nevertheless causes his scheme to sometimes be described as a peculiar kind of dualism.[10]

Anaxagoras' concept of nous was distinct from later platonic and neoplatonic cosmologies in many ways, which were also influenced by Eleatic, Pythagorean and other pre Socratic ideas, as well as the Socratics themselves.

In ancient Indian Philosophy also, a "higher mind", came to be considered to be a property of the cosmos as a whole.[12]

[edit] Socratic philosophy

[edit] Xenophon

Xenophon, the less famous of the two students of Socrates who wrote about him recorded that he taught his students a kind of teleological justification of piety and respect for divine order in nature. This has been described as an "intelligent design" argument for the existence of God, in which nature has its own nous. For example in his Memorabilia 1.4.8 he describes Socrates asking a friend sceptical of religion "Are you, then, of the opinion that intelligence (nous) alone exists nowhere and that you by some good chance seized hold of it, while - as you think - those surpassingly large and infinitely numerous things [all the earth and water] are in such orderly condition through some senselessness?" and later in the same discussion he compares the nous which directs each person's body, to the good sense (phronēsis) of the god which is in everything, arranging things to its pleasure. (1.4.17).[13] Plato describes Socrates making the same argument in his Philebus 28d, using the same words nous and phronēsis.[14]

Plato used the word nous in many ways which were not unusual in the everyday Greek of the time, and often simply meant "good sense".[15] On the other hand, in some of his dialogues it is described by key characters in a higher sense, which was apparently already common. In his Philebus 28c he has Socrates say that "all philosophers agree—whereby they really exalt themselves—that mind (nous) is king of heaven and earth. Perhaps they are right." and later states that the ensuing discussion "confirms the utterances of those who declared of old that mind (nous) always rules the universe".[16]

In his Phaedo, Plato's teacher Socrates is made to say just before dying that his discovery of Anaxagoras' concept of a cosmic nous as the cause of the order of things, was an important turning point for him. But he also expressed disagreement with Anaxagoras' understanding of the implications of his own doctrine, because of Anaxagoras' materialist understanding of causation. Socrates said that Anaxagoras would "give voice and air and hearing and countless other things of the sort as causes for our talking with each other, and should fail to mention the real causes, which are, that the Athenians decided that it was best to condemn me".[17] On the other hand Socrates seems to suggest that he also failed to develop a fully satisfactory teleological and dualistic understanding of a mind of nature, whose aims represent the good things which all parts of nature aim at.

Concerning the nous of individuals, the source of understanding, in opposition to Anaxagoras Plato is also widely understood to have accepted ideas from Parmenides which affect his explanation of nous. Like Parmenides, Plato argued that relying on sense perception can never lead to true knowledge, only opinion. Instead, Plato's more philosophical characters argue that nous must somehow perceive truth directly in the ways gods and daimons perceive. What our mind sees directly in order to really understand things must not be the constantly changing material things, but un-changing entities that exist in a different way, the so called "forms" or "ideas". However he knew that contemporary philosophers often argued (as in modern science) that nous and perception are just two aspects of one physical activity, and that perception is the source of knowledge and understanding (not the other way around).

Just exactly how Plato believed that people 's nous lets them come to understand things in any way which improves upon sense perception is a subject of long running discussion and debate. On the one hand, in the Republic Plato's Socrates, in the so-called "metaphor of the sun", and "allegory of the cave" sections describes people as being able to see more clearly because of something from outside themselves, something like when sun shines, helping eyesight. This illumination of the intellect shines from the Form of the Good. On the other hand, in the Meno for example, Plato's Socrates explains the theory of anamnesis whereby people are born with ideas already in their soul, which they somehow remember from previous lives. Both theories were to be highly influential.

As in Xenophon, and apparently based upon Socrates, Plato frequently describes the soul in a political way, with ruling parts, and parts which are by nature meant to be ruled. Nous is associated with the rational (logistikon) part of the individual human soul, which by nature should rule. In his Republic, in the so-called "analogy of the divided line", it has a special function within this rational part. Plato tended to treat nous as the only immortal part of the soul.

Concerning the cosmos, in the Timaeus, the title character also tells a likely story in which nous is responsible for the creative work of the demiurge or maker who brought rational order to our universe. This craftsman imitated what he perceived in the world of eternal Forms. In the Philebus Socrates argues that nous in individual humans must share in a cosmic nous, in the same way that human bodies are made up of small parts of the elements found in the rest of the universe. And this nous must be in the genos of being a cause of all particular things as particular things.[18]

[edit] Aristotle

Like Plato, Aristotle saw the nous or intellect of an individual as an intuitive understanding, distinguished from sense perception.[19] Like Plato, Aristotle linked nous to logos (reason) as uniquely human, but he also distinguished nous from logos, thereby distinguishing the faculty for setting definitions from the faculty which uses them to reason with.[20] In his Nicomachean Ethics, Book VI Aristotle divides the soul (psuchē) into two parts, one which has reason and one which does not, but then divides the part which has reason into the reasoning (logistikos) part itself which is lower, and the higher "knowing" (epistēmonikos) part which contemplates general principles (archai). Nous, he states, is the source of the first principles or sources (archai) of definitions, and it develops naturally as people get older. This he explains after first comparing the four other truth revealing capacities of soul: technical know how (technē), logically deduced knowledge (epistēmē, sometimes translated as "scientific knowledge"), practical wisdom (phronēsis), and lastly theoretical wisdom (sophia), which is defined by Aristotle as the combination of nous and epistēmē. All of these others apart from nous involve reason (logos).

And intellect [

nous] is directed at what is ultimate on both sides, since it is intellect and not reason [

logos] that is directed at both the first terms [

horoi] and the ultimate particulars, on the one side at the changeless first terms in demonstrations, and on the other side, in thinking about action, at the other sort of premise, the variable particular; for these particulars are the sources [

archai] from which one discerns that for the sake of which an action is, since the universals are derived from the particulars. Hence intellect is both a beginning and an end, since the demonstrations that are derived from these particulars are also about these. And of these one must have perception, and this perception is intellect.

[21]

Aristotle's philosophical works continue many of the same Socratic themes as his teacher Plato. Amongst the new proposals he made was a way of explaining causality, and nous is an important part of his explanation. As mentioned above, Plato criticized Anaxagoras' materialism, or understanding that the intellect of nature only set the cosmos in motion, but is no longer seen as the cause of physical events. Aristotle explained that the changes of things can be described in terms of four causes at the same time. Two of these four causes are similar to the materialist understanding: each thing has a material which causes it to be how it is, and some other thing which set in motion or initiated some process of change. But at the same time according to Aristotle each thing is also caused by the natural forms they are tending to become, and the natural ends or aims, which somehow exist in nature as causes, even in cases where human plans and aims are not involved. These latter two causes, are concepts no longer used in modern science, encompassing the continuing effect of the ordering principle of nature itself. Aristotle's special description of causality is especially apparent in the natural development of living things. It leads to a method whereby Aristotle analyses causation and motion in terms of the potentialities and actualities of all things, whereby all matter possesses various possibilities or potentialities of form and end, and these possibilities become more fully real as their potential forms become actual or active reality (something they will do on their own, by nature, unless stopped because of other natural things happening). For example a stone has in its nature the potentiality of falling to the earth and it will do so, and actualize this natural tendency, if nothing is in the way.

Aristotle analyzed thinking in the same way. For him, the possibility of understanding rests on the relationship of intellect and sense perception. Aristotle's remarks on the concept of what came to be called the "active intellect" and "passive intellect" (along with various other terms) are amongst "the most intensely studied sentences in the history of philosophy".[22] The terms are derived from a single passage in Aristotle's De Anima, Book III. Following is the translation of one of those passages[23] with some key Greek words shown in square brackets.

...since in nature one thing is the material [hulē] for each kind [genos] (this is what is in potency all the particular things of that kind) but it is something else that is the causal and productive thing by which all of them are formed, as is the case with an art in relation to its material, it is necessary in the soul [psuchē] too that these distinct aspects be present;

the one sort is intellect [nous] by becoming all things, the other sort by forming all things, in the way an active condition [hexis] like light too makes the colors that are in potency be at work as colors [to phōs poiei ta dunamei onta chrōmata energeiai chrōmata].

This sort of intellect [which is like light in the way it makes potential things work as what they are] is separate, as well as being without attributes and unmixed, since it is by its thinghood a being-at-work, for what acts is always distinguished in stature above what is acted upon, as a governing source is above the material it works on.

Knowledge [epistēmē], in its being-at-work, is the same as the thing it knows, and while knowledge in potency comes first in time in any one knower, in the whole of things it does not take precedence even in time.

This does not mean that at one time it thinks but at another time it does not think, but when separated it is just exactly what it is, and this alone is deathless and everlasting (though we have no memory, because this sort of intellect is not acted upon, while the sort that is acted upon is destructible), and without this nothing thinks.

The passage tries to explain "how the human intellect passes from its original state, in which it does not think, to a subsequent state, in which it does" according to his distinction between potentiality and actuality.[22] Aristotle says that the passive intellect receives the intelligible forms of things, but that the active intellect is required to make the potential knowledge into actual knowledge, in the same way that light makes potential colors into actual colors. As Davidson remarks:

Just what Aristotle meant by potential intellect and active intellect - terms not even explicit in the De anima and at best implied - and just how he understood the interaction between them remains moot. Students of the history of philosophy continue to debate Aristotle's intent, particularly the question whether he considered the active intellect to be an aspect of the human soul or an entity existing independently of man.[22]

The passage is often read together with Metaphysics, Book XII, ch.7-10, where Aristotle makes nous as an actuality a central subject within a discussion of the cause of being and the cosmos. In that book, Aristotle equates active nous, when people think and their nous becomes what they think about, with the "unmoved mover" of the universe, and God: "For the actuality of thought (nous) is life, and God is that actuality; and the essential actuality of God is life most good and eternal."[24] Alexander of Aphrodisias, for example, equated this active intellect which is God with the one explained in De Anima, while Themistius thought they could not be simply equated. (See below.)

Like Plato before him, Aristotle believes Anaxagoras' cosmic nous implies and requires the cosmos to have intentions or ends: "Anaxagoras makes the Good a principle as causing motion; for Mind (nous) moves things, but moves them for some end, and therefore there must be some other Good—unless it is as we say; for on our view the art of medicine is in a sense health."[25]

In the philosophy of Aristotle the soul (psyche) of a body is what makes it alive, and is its actualized form; thus, every living thing, including plant life, has a soul. The mind or intellect (nous) can be described variously as a power, faculty, part, or aspect of the human soul. It should be noted that for Aristotle soul and intellect are not the same. He did not rule out the possibility that intellect might survive without the rest of the soul, as in Plato, but plants have a 'nutritive' soul without a nous. In his Generation of Animals Aristotle specifically says that while other parts of the soul come from the parents, physically, the nous, must come from outside, into the body, because it is divine or godly, and it has nothing in common with the energeia of the body.[26] This was yet another passage which Alexander of Aphrodisias would link to those mentioned above from De Anima and the Metaphysics in order to understand Aristotle's intentions.

[edit] Post Aristotelian classical theories

Until the early modern era, much of the discussion which has survived today concerning nous or intellect, in Europe, Africa and the Middle East, concerned how to correctly interpret Aristotle and Plato. However, at least during the classical period, materialist philosophies, more similar to modern science, such as Epicureanism, were still relatively common also. The Epicureans believed that the bodily senses themselves were not the cause of error, but the interpretations can be. The term prolepsis was used by Epicureans to describe the way the mind forms general concepts from sense perceptions.

To the Stoics, more like Heraclitus than Anaxagoras, order in the cosmos comes from an entity called logos, the cosmic reason. But as in Anaxagoras this cosmic reason, like human reason but higher, is connected to the reason of individual humans. The Stoics however, did not invoke incorporeal causation, but attempted to explain physics and human thinking in terms of matter and forces. As in Aristotelianism, they explained the interpretation of sense data requiring the mind to be stamped or formed with ideas. However, they did not propose any in-born or acquired equivalent of the "active intellect" in order to explain how people could know understand things. Nous for them is soul "somehow disposed" (pôs echon), the soul being somehow disposed pneuma, which is fire or air or a mixture. As in Plato, they treated nous as the ruling part of the soul.[27]

Plutarch criticized the Stoic idea of nous being corporeal, and agreed with Plato that the soul is more divine than the body while nous (mind) is more divine than the soul.[27] The mix of soul and body produces pleasure and pain; the conjunction of mind and soul produces reason which is the cause or the source of virtue and vice. (From: “On the Face in the Moon”) [28]

Albinus was one of the earliest authors to equate Aristotle's nous as prime mover of the Universe, with Plato's Form of the Good.[27]

[edit] Alexander of Aphrodisias

Alexander of Aphrodisias was a Peripatetic (Aristotelian) and his On the Soul (referred to as De anima in its traditional Latin title), explained that by his interpretation of Aristotle, potential intellect in man, that which has no nature but receives on from the active intellect, is material, and also called the "material intellect" (nous hulikos) and it is inseparable from the body, being "only a disposition" of it.[29] He argued strongly against the doctrine of immortality. On the other hand, he identified the active intellect (nous poietikos), through whose agency the potential intellect in man becomes actual, not with anything from within people, but with the divine creator itself. In the early Renaissance his doctrine of the soul's mortality was adopted by Pietro Pomponazzi against the Thomists and the Averroists. For him, the only possible human immortality is an immortality of a detached human thought, more specifically when the nous has as the object of its thought the active intellect itself, or another incorporeal intelligible form.[30]

Alexander was also responsible for influencing the development of several more technical terms concerning the intellect, which became very influential amongst the great Islamic philosophers, Al-Farabi, Avicenna, and Averroes.

- The intellect in habitu is a stage in which the human intellect has taken possession of a repertoire of thoughts, and so is potentially able to think those thoughts, but is not yet thinking these thoughts.

- The intellect from outside, which became the "acquired intellect" in Islamic philosophy, describes the incorporeal active intellect which comes from outside man, and becomes an object thought, making the material intellect actual and active. This term may have come from a particularly expressive translation of Alexander into Arabic. Plotinus also used such a term.[31] In any case, in Al-Farabi and Avicenna, the term took on a new meaning, distinguishing it from the active intellect in any simple sense - an ultimate stage of the human intellect where the a kind of close relationship (a "conjunction") is made between a person's active intellect and the transcendental nous itself.

[edit] Themistius

Themistius, another influential commentator on this matter, understood Aristotle differently, stating that the passive or material intellect does "not employ a bodily organ for its activity, is wholly unmixed with the body, impassive, and separate [from matter]".[32] This means the human potential intellect, and not only the active intellect, is an incorporeal substance, or a disposition of incorporeal substance. For Themistius, the human soul becomes immortal "as soon as the active intellect intertwines with it at the outset of human thought".[30]

This understanding of the intellect was also very influential for Al-Farabi, Avicenna, and Averroes, and "virtually all Islamic and Jewish philosophers".[33] On the other hand concerning the active intellect, like Alexander and Plotinus, he saw this as a transcendent being existing above and outside man. Differently from Alexander, he did not equate this being with the first cause of the Universe itself, but something lower.[34] However he equated it with Plato's Idea of the Good.[35]

[edit] Plotinus and neoplatonism

Of the later Greek and Roman writers Plotinus, the intiator of neoplatonism, is particularly significant. Like Alexander of Aphrodisias and Themistius, he saw himself as a commentator explaining the doctrines of Plato and Aristotle. But in his Enneads he went further than those authors, often working from passages which had been presented more tentatively, possibly inspired partly by earlier authors such as the neopythagorean Numenius of Apamea. Neoplatonism provided a major inspiration to discussion concerning the intellect in late classical and medieval philosophy, theology and cosmology.

In neoplatonism there exists several levels or hypostases of being, including the natural and visible world as a lower part.

- The Monad or "the One" sometimes also described as "the Good", based on the concept as it is found in Plato. This is the dunamis or possibility of existence. It causes the other levels by emanation.

- The Nous (usually translated as "Intellect", or "Intelligence" in this context, or sometimes "mind" or "reason") is described as God, or more precisely an image of God, often referred to as the Demiurge. It thinks its own contents, which are thoughts, equated to the Platonic ideas or forms (eide). The thinking of this Intellect is the highest activity of life. The actualization (energeia) of this thinking is the being of the forms. This Intellect is the first principle or foundation of existence. The One is prior to it, but not in the sense that a normal cause is prior to an effect, but instead Intellect is called an emanation of the One. The One is the possibility of this foundation of existence.

- Soul (psuchē). The soul is also an energeia: it acts upon or actualizes its own thoughts and creates "a separate, material cosmos that is the living image of the spiritual or noetic Cosmos contained as a unified thought within the Intelligence". So it is the soul which perceives things in nature physically, which it understands to be reality. Soul in Plotinus plays a role similar to the potential intellect in Aristotelian terminology.[27]

- Lowest is matter.

This was based largely upon Plotinus' reading of Plato, but also incorporated many Aristotelian concepts, including the Unmoved Mover as energeia.[36] They also incorporated a theory of anamnesis, or knowledge coming from the past lives of our immortal souls, like that found in some of Plato's dialogues.

Later Platonists distinguished a hierarchy of three separate manifestations of nous, like Numenius of Apamea had.[37] Notable later neoplatonists include Porphyry and Proclus.

[edit] Gnosticism

Gnosticism was a late classical movement which incorporated ideas inspired by neoplatonism and neopythagoreanism, but which was more syncretic religious movement than an accepted philosophical movement.

[edit] Valentinus

In the Valentinian system, Nous is the first male Aeon. Together with his conjugate female Aeon, Aletheia (truth), he emanates from the Propator Bythos and his coeternal Ennoia or Sige; and these four form the primordial Tetrad. Like the other male Aeons he is sometimes regarded as androgynous, including in himself the female Aeon who is paired with him. He is the Only Begotten; and is styled the Father, the Beginning of all, inasmuch as from him are derived immediately or mediately the remaining Aeons who complete the Ogdoad (eight), thence the Decad (ten), and thence the Dodecad (twenty); in all thirty, Aeons constituting the Pleroma. He alone is capable of knowing the Propator; but when he desired to impart like knowledge to the other Aeons, was withheld from so doing by Sige. When Sophia (wisdom), youngest Aeon of the thirty, was brought into peril by her yearning after this knowledge, Nous was foremost of the Aeons in interceding for her. From him, or through him from the Propator, Horos was sent to restore her. After her restoration, Nous, according to the providence of the Propator, produced another pair, Christ and the Holy Spirit, "in order to give fixity and steadfastness (eis pēxin kai stērigmon) to the Pleroma." For this Christ teaches the Aeons to be content to know that the Propator is in himself incomprehensible, and can be perceived only through the Only Begotten (Nous).[38]

[edit] Basilides

A similar conception of Nous appears in the later teaching of the Basilidean School, according to which he is the first begotten of the Unbegotten Father, and himself the parent of Logos, from whom emanate successively Phronesis, Sophia, and Dunamis. But in this teaching Nous is identified with Christ, is named Jesus, is sent to save those that believe, and returns to Him who sent him, after a passion which is apparent only,—Simon the Cyrenian being substituted for him on the cross.[39] It is probable, however, that Nous had a place in the original system of Basilides himself; for his Ogdoad, "the great Archon of the universe, the ineffable"[40] is apparently made up of the five members named by Irenaeus (as above), together with two whom we find in Clement,[41] Dikaiosyne and Eirene,—added to the originating Father.

[edit] Simon Magus

Main article:

Simon MagusThe antecedent of these systems is that of Simon Magus,[42] of whose six "roots" emanating from the Unbegotten Fire, Nous is first. The correspondence of these "roots" with the first six Aeons which Valentinus derives from Bythos, is noted by Hippolytus.[43] Simon says in his Apophasis Megalē,[44]

There are two offshoots of the entire ages, having neither beginning nor end.... Of these the one appears from above, the great power, the Nous of the universe, administering all things, male; the other from beneath, the great Epinoia, female, bringing forth all things.

To Nous and Epinoia correspond Heaven and Earth, in the list given by Simon of the six material counterparts of his six emanations. The identity of this list with the six material objects alleged by Herodotus[45] to be worshipped by the Persians, together with the supreme place given by Simon to Fire as the primordial power, leads us to look to Persia for the origin of these systems in one aspect. In another, they connect themselves with the teaching of Pythagoras and of Plato.

[edit] Gospel of Mary

Main article:

Gospel of MaryAccording to the Gospel of Mary, Jesus himself articulates the essence of Nous:

"There where is the nous, lies the treasure." Then I said to him: "Lord, when someone meets you in a Moment of Vision, is it through the soul [psuchē] that they see, or is it through the spirit [pneuma]?" The Teacher answered: "It is neither through the soul nor the spirit, but the nous between the two which sees the vision..."

—The Gospel of Mary, p. 10

[edit] Medieval Islamic, Jewish, and Christian Averroist philosophy

During the middle ages, philosophy itself was in many places seen as opposed to the prevailing monotheistic religions, Islam, Christianity and Judaism. The strongest philosophical tradition for some centuries was amongst Islamic philosophers, who later came to strongly influence the late medieval philosophers of western Christendom, and the Jewish diaspora in the Mediterranean area. While there were earlier Muslim philosophers such as Al Kindi, chronologically the three most influential concerning the intellect were Al Farabi, Avicenna, and finally Averroes, a westerner who lived in Spain and was highly influential in the late middle ages amongst Jewish and Christian philosophers.

[edit] Al Farabi

The exact precedents of Al Farabi's influential philosophical scheme, in which nous (Arabic 'aql) plays an important role, are no longer perfectly clear because of the great loss of texts in the middle ages which he would have had access to. He was apparently innovative in at least some points. He was clearly influenced by the same late classical world as neoplatonism, neopythagoreanism, but exactly how is less clear. Plotinus, Themistius and Alexander of Aphrodisias are generally accepted to have been influences. However while these three all placed the active intellect "at or near the top of the hierarchy of being", Al Farabi was clear in making it the lowest ranking in a series of distinct transcendental intelligences. He is the first known person to have done this in a clear way.[46] He was also the first philosopher known to have assumed the existence of a causal hierarchy of celestial spheres, and the incorporeal intelligences parallel to those spheres.[47] Al Farabi also fitted an explanation of prophecy into this scheme, in two levels. According to Davidson (p. 59):

The lower of the two levels, labeled specifically as "prophecy" (nubuwwa), is enjoyed by men who have not yet perfected their intellect, whereas the higher, which Alfarabi sometimes specifically names "revelation" (w-ḥ-y), comes exclusively to those who stand at the stage of acquired intellect.

This happens in the imagination (Arabic mutakhayyila; Greek phantasia), a faculty of the mind already described by Aristotle, which Al Farabi described as serving the rational part of the soul (Arabic 'aql; Greek nous). This faculty of imagination stores sense perceptions (maḥsūsāt), disassembles or recombines them, creates figurative or symbolic images (muḥākāt) of them which then appear in dreams, visualizes present and predicted events in a way different from conscious deliberation (rawiyya). This is under the influence, according to Al Farabi, of the active intellect. Theoretical truth can only be received by this faculty in a figurative or symbolic form, because the imagination is a physical capability and can not receive theoretical information in a proper abstract form. This rarely comes in a waking state, but more often in dreams. The lower type of philosophy is the best possible for the imaginative faculty, but the higher type of prophecy requires not only a receptive imagination, but also the condition of an "acquired intellect", where the human nous is in "conjunction" with the active intellect in the sense of God. Such a prophet is also a philosopher. When a philosopher-prophet has the necessary leadership qualities, he becomes philosopher-king.[48]

[edit] Avicenna

In terms of cosmology, according to Davidson (p. 82) "Avicenna's universe has a structure virtually identical with the structure of Alfarabi's" but there are differences in details. As in Al Farabi, there are several levels of intellect, intelligence or nous, each of the higher ones being associated with a celestial sphere. Avicenna however details three different types of effect which each of these higher intellects has, each "thinks" both the necessary existence and the possible being of the intelligence one level higher. And each "emanates" downwards the body and soul of its own celestial sphere, and also the intellect at the next lowest level. The active intellect, as in Alfarabi, is the last in the chain. Avicenna sees active intellect as the cause not only of intelligible thought and the forms in the "sublunar" world we people live, but also the matter. (In other words, three effects.)[49]

Concerning the workings of the human soul, Avicenna, like Al Farabi, sees the "material intellect" or potential intellect as something that is not material. He believed the soul was incorporeal, and the potential intellect was a disposition of it which was in the soul from birth. As in Al Farabi there are two further stages of potential for thinking, which are not yet actual thinking, first the mind acquires the most basic intelligible thoughts which we can not think in any other way, such as "the whole is greater than the part", then comes a second level of derivative intelligible thoughts which could be thought.[49] Concerning the actualization of thought, Avicenna applies the term "to two different things, to actual human thought, irrespective of of the intellectual progress a man has made, and to actual thought when human intellectual development is complete", as in Al Farabi.[50]

When reasoning in the sense of deriving conclusions from syllogisms, Avicenna says people are using a physical "cogitative" faculty (mufakkira, fikra) of the soul, which can err. The human cogitative faculty is the same as the "compositive imaginative faculty (mutakhayyila) in reference to the animal soul".[51] But some people can use "insight" to avoid this step and derive conclusions directly by conjoining with the active intellect.[52]

Once a thought has been learned in a soul, the physical faculties of sense perception and imagination become unnecessary, and as a person acquires more thoughts, their soul becomes less connected to their body.[53] For Avicenna, differently to the normal Aristotelian position, all of the soul is by nature immortal. But the level of intellectual development does affect the type of afterlife that the soul can have. Only a soul which has reached the highest type of conjunction with the active intellect can form a perfect conjunction with it after the death of the body, and this is a supreme eudaimonia. Lesser intellectual achievement means a less happy or even painful afterlife.[54]

Concerning prophecy, Avicenna identifies a broader range of possibilities which fit into this model, which is still similar to that of Al Farabi.[55]

[edit] Averroes

Main articles:

Averroes and

AverroismAverroes came to be regarded even in Europe as "the Commentator" to "the Philosopher", Aristotle, and his study of the questions surrounding the nous were very influential amongst Jewish and Christian philosophers, with some aspects being quite controversial. According to Herbert Davidson, Averroes' doctrine concerning nous can be divided into two periods. In the first, neoplatonic emanationism, not found in the original works of Aristotle, was combined with a naturalistic explanation of the human material intellect. "It also insists on the material intellect's having an active intellect as a direct object of thought and conjoining with the active intellect, notions never expressed in the Aristotelian canon." It was this presentation which Jewish philosophers such as Moses Narboni and Gersonides understood to be Averroes'. In the later model of the universe, which was transmitted to Christian philosophers, Averroes "dismisses emanationism and explains the generation of living beings in the sublunar world naturalistically, all in the name of a more genuine Aristotelianism. Yet it abandons the earlier naturalistic conception of the human material intellect and transforms the material intellect into something wholly un-Aristotelian, a single transcendent entity serving all mankind. It nominally salvages human conjunction with the active intellect, but in words that have little content."[56]

This position, that humankind shares one active intellect, was taken up by Parisian philosophers such as Siger of Brabant, but also widely rejected by philosophers such as Albertus Magnus, Thomas Aquinas, Ramon Lull, and Duns Scotus. Despite being widely considered heretical, the position was later defended by many more European philosophers including John of Jandun, who was the primary link bringing this doctrine from Paris to Bologna. After him this position continued to be defended and also rejected by various writers in northern Italy. In the 16th century it finally became a less common position after the renewal of an "Alexandrian" position based on that of Alexander of Aphrodisias, associated with Pietro Pomponazzi.[57]

[edit] Christianity

The Christian New Testament makes mention of the nous or noos in Romans 7:23, 12:2; 1 Corinthians 14:14, 14:19; Ephesians 4:17, 4:23; 2 Thessalonians 2:2; and Revelation 17:9. In the writings of the Christian fathers a sound or pure nous is considered essential to the cultivation of wisdom.[58]

[edit] Philosophers influencing western Christianity

While philosophical works were not commonly read or taught in the early middle ages in most of Europe, the works of authors like Boethius and Augustine of Hippo formed an important exception. Both were influenced by neoplatonism, and were amongst the older works that were still known in the time of the Carolingian Renaissance, and the beginnings of Scholasticism.

In his early years he was heavily influenced by Manichaeism and afterward by the Neo-Platonism of Plotinus.[59] After his conversion to Christianity and baptism (387), Augustine developed his own approach to philosophy and theology, accommodating a variety of methods and different perspectives.[60]

Augustine used neoplatonism selectively. He used both the neoplatonic Nous, and the Platonic Form of the Good (or "The Idea of the Good") as equivalent terms for the Christian God, or at least for one particular aspect of God. For example, God, nous, can act directly upon matter, and not only through souls, and concerning the souls through which it works upon the world experienced by humanity, some are treated as angels.[27]

Scholasticism becomes more clearly defined much later, as the peculiar native type of philosophy in medieval catholic Europe. In this period, Aristotle became "the Philosopher", and scholastic philosophers, like their Jewish and Muslim contemporaries, studied the concept of the intellectus on the basis not only of Aristotle, but also late classical interpreters like Augustine and Boethius. A European tradition of new and direct interpretations of Aristotle developed which was eventually strong enough to argue with partial success against some of the interpretations of Aristotle from the islamic world, most notably Averroes' doctrine of their being one "active intellect" for all humanity. Notable "Catholic" (as opposed to Averroist) Aristotelians included Albertus Magnus and Thomas Aquinas, the founder Thomism, which exists to this day in various forms. Concerning the nous, Thomism agrees with those Aristotelians who insist that the intellect is immaterial and separate from any bodily organs, but as per Christian doctrine, the whole of the human soul is immortal, not only the intellect.

[edit] Eastern Orthodox

The human nous in Eastern Orthodox Christianity is the "eye of the heart or soul" or the "mind of the heart".[61][62][63][64] The soul of man, is created by God in His image, man's soul is intelligent and noetic. St Thalassios wrote that God created beings "with a capacity to receive the Spirit and to attain knowledge of Himself; He has brought into existence the senses and sensory perception to serve such beings". Eastern Orthodox Christians hold that God did this by creating mankind with intelligence and noetic faculties.[65]

Human reasoning is not enough: there will always remain an "irrational residue" which escapes analysis and which can not be expressed in concepts: it is this unknowable depth of things, that which constitutes their true, indefinable essence that also reflects the origin of things in God. In Eastern Christianity it is by faith or intuitive truth that this component of an objects existence is grasp.[66] Though God through his energies draws us to him, his essence remains inaccessible.[66] The operation of faith being the means of free will by which mankind faces the future or unknown, these noetic operations contained in the concept of insight or noesis.[67] Faith (pistis) is therefore sometimes used interchangeably with noesis in Eastern Christianity.

Angels have intelligence and nous, whereas men have reason both logos and dianoia, nous and sensory perception. This follows the idea that man is a microcosm and an expression of the whole creation or macrocosmos. The human nous was darkened after the Fall of Man (which was the result of the rebellion of reason against the nous),[68] but after the purification (healing or correction) of the nous (achieved through ascetic practices like hesychasm), the human nous (the "eye of the heart") will see God's uncreated Light (and feel God's uncreated love and beauty, at which point the nous will start the unceasing prayer of the heart) and become illuminated, allowing the person to become an orthodox theologian.[61][69][70]

In this belief, the soul is created in the image of God. Since God is Trinitarian, Mankind is Nous, reason both logos and dianoia and Spirit. The same is held true of the soul (or heart): it has nous, word and spirit. To understand this better first an understanding of St Gregory Palamas's teaching that man is a representation of the trinitarian mystery should be addressed. This holds that God is not meant in the sense that the Trinity should be understood anthropomorphically, but man is to be understood in a triune way. Or, that the Trinitarian God is not to be interpreted from the point of view of individual man, but man is interpreted on the basis of the Trinitarian God. And this interpretation is revelatory not merely psychological and human. This means that it is only when a person is within the revelation, as all the saints lived, that he can grasp this understanding completely (see theoria). The second presupposition is that mankind has and is composed of nous, word and spirit like the trinitarian mode of being. Man's nous, word and spirit are not hypostases or individual existences or realities, but activities or energies of the soul. Were as in the case with God or the Persons of the Holy Trinity each are indeed hypostases. So these three components of each individual man are 'inseparable from one another' but they do not have a personal character" when in speaking of the being or ontology that is mankind. The nous as the eye of the soul, which some Fathers also call the heart, is the center of man and is where true (spiritual) knowledge is validated. This is seen as true knowledge which is "implanted in the nous as always co-existing with it".[71]

[edit] Early modern philosophy

The so called "early modern" philosophers of western Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries established arguments which lead to the establishment of modern science as a methodical approach to improve the welfare of humanity by learning to control nature. As such, speculation about metaphysics, which can not be used for anything practical, and which can never be confirmed against the reality we experience, started to be deliberately avoided, especially according to the so called "empiricist" arguments of philosophers such as Bacon, Hobbes, Locke and Hume. The Latin motto "nihil in intellectu nisi prius fuerit in sensu" (nothing in the intellect without first being in the senses) has been described as the "guiding principle of empiricism" in the Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy.[72] (This was in fact an old Aristotelian doctrine, which they took up, but of course as discussed above Aristotelians still believed that the senses on their own were not enough to explain the mind.)

These philosophers explain the intellect as something developed from experience of sensations, being interpreted by the brain in a physical way, and nothing else, which means that absolute knowledge is impossible. For Bacon, Hobbes and Locke, who wrote in both English and Latin, "intellectus" was translated as "understanding".[73] Far from seeing it as secure way to perceive the truth about reality, Bacon, for example, actually named the intellectus in his Novum Organum as a major source of wrong conclusions, because it is biased in many ways, for example towards over-generalizing. For this reason modern science should be methodical, in order not to be mislead by the weak human intellect. The intellect or understanding was therefore the subject of Locke's Essay Concerning Human Understanding.[74] These philosophers also tended not to emphasize the distinction between reason and intellect, describing the peculiar universal or abstract definitions of human understanding as being man-made and resulting from reason itself.[75] In the case of Hume the distinctness or peculiarly of human understanding and reason, compared to other types of associative or imaginative thinking found in some other animals, are even questioned.[76] In modern science during this time, Newton is sometimes described as more empiricist compared to Leibniz.

On the other hand, into modern times some philosophers have continued to propose that the human mind has an in-born ("a priori") ability to know the truth conclusively, and these need to argue that the human mind has direct and intuitive ideas about nature, and this means it can not be limited entirely to what can be known from sense perception. Amongst the early modern philosophers some such as Descartes, Spinoza, Leibniz, and Kant, tend to be distinguished from the empiricists as rationalists, and to some extent at least some of them are called idealists, and their writings on the intellect or understanding present various doubts about empiricism, and in some cases they argued for positions which appear more similar to those of medieval and classical philosophers.

The first in this series of modern rationalists, Descartes, is credited with defining a "mind-body problem" which is a major subject of discussion for university philosophy courses. According to the presentation his 2nd Meditation, the human mind and body are different in kind, and while the human body works like a clockwork mechanism, and its workings include memory and imagination, the real human is the thinking being, a soul. Descartes explicitly refused to divide this soul into its traditional parts such as intellect and reason, saying that these things were indivisible aspects of the soul. Descartes was therefore a dualist, but very much in opposition to traditional Aristotelian dualism. In his 6th Meditation he deliberately uses traditional terms and states that his active faculty of giving ideas to his thought must be corporeal, because the things perceived are clearly external to his own thinking and corporeal, while his passive faculty must be incorporeal (unless God is deliberately deceiving us, and then in this case the active faculty would be from God). This is the opposite of the traditional explanation found for example in Alexander of Aphrodisias and discussed above, for whom the passive intellect is material, while the active intellect is not. One result is that in many Aristotelian conceptions of the nous, for example that of Thomas Aquinas, the senses are still a source of all the intellect's conceptions. However, with the strict separation of mind and body proposed by Descartes, it becomes possible to propose that there can be thought about objects never perceived with the body's senses, such as a thousand sided geometrical figure. Gassendi objected to this distinction between the imagination and the intellect in Descartes.[77] Hobbes also objected, and according to his own philosophical approach asserted that the "triangle in the mind comes from the triangle we have seen" and "essence in so far as it is distinguished from existence is nothing else than a union of names by means of the verb is". Descartes, in his reply to this objection insisted that this traditional distinction between essence and existence is "known to all".[78]

His contemporary Blaise Pascal, criticised him in similar words to those used by Plato's Socrates concerning Anaxagoras, discussed above, saying that "I cannot forgive Descartes; in all his philosophy, Descartes did his best to dispense with God. But Descartes could not avoid prodding God to set the world in motion with a snap of his lordly fingers; after that, he had no more use for God."[79]

Descartes argued that when the intellect does a job of helping people interpret what they perceive, not with the help of an intellect which enters from outside, but because each human mind comes into being with innate God-given ideas, more similar then, to Plato's theory of anamnesis, only not requiring reincarnation. Apart from such examples as the geometrical definition of a triangle, another example is the idea of God, according to the 3rd Meditation. Error, according to the 4th Meditation, comes about because people make judgments about things which are not in the intellect or understanding. This is possible because the human will, being free, is not limited like the human intellect.

Spinoza, though considered a Cartesian and a rationalist, rejected Cartesian dualism and idealism. In his "pantheistic" approach, explained for example in his Ethics, God is the same as nature, the human intellect is just the same as the human will. The divine intellect of nature is quite different from human intellect, because it is finite, but Spinoza does accept that the human intellect is a part of the infinite divine intellect.

Leibniz, in comparison to the guiding principle of the empiricists described above, added some words ""nihil in intellectu nisi prius fuerit in sensu, nisi intellectus ipsi" (nothing in the intellect without first being in the senses except the intellect itself).[72] Despite being at the forefront of modern science, and modernist philosophy, in his writings he still referred to the active and passive intellect, a divine intellect, and the immortality of the active intellect.

Berkeley, partly in reaction to Locke, also attempted to reintroduce an "immaterialism" into early modern philosophy (later referred to as "subjective idealism" by others). He argued that individuals can only know sensations and ideas of objects, not abstractions such as "matter", and that ideas depend on perceiving minds for their very existence. This belief later became immortalized in the dictum, "esse est percipi" ("to be is to be perceived"). As in classical and medieval philosophy, Berkeley believed understanding had to be explained by divine intervention, and that all our ideas are put in our mind by God.

Hume accepted some of Berkeley's corrections of Locke, but in answer insisted, as had Bacon and Hobbes, that absolute knowledge is not possible, and that all attempts to show how it could be possible have logical problems. Hume's writings remain highly influential on all philosophy afterwards, and for example considered by Kant to have shaken him from an intellectual slumber.

Kant, a turning point in modern philosophy, agreed with some classical philosophers and Leibniz that the intellect itself, although it needed sensory experience for understanding to begin, needs something else in order to make sense of the incoming sense information. In his formulation the intellect (Verstand) has "a priori" or innate principles which it has before thinking even starts. Kant represents the starting point of German Idealism and a new phase of modernity, while empiricist philosophy has also continued beyond Hume to the present day.

[edit] More recent modern philosophy and science

One of the results of the early modern philosophy has been the increasing creation of specialist fields of science, in areas that were once considered part of philosophy, and infant cognitive development and perception now tend to be discussed now more within the sciences of psychology and neuroscience than in philosophy.

Modern mainstream thinking on the mind is not dualist, and sees anything innate in the mind as being a result of genetic and developmental factors which allow the mind to develop. Overall it accepts far less innate "knowledge" (or clear pre-dispositions to particular types of knowledge) than most of the classical and medieval theories derived from philosophers such as Plato, Aristotle, Plotinus and Al Farabi.

Apart from discussions about the history of philosophical discussion on this subject, contemporary philosophical discussion concerning this point has continued concerning what the ethical implications are of the different alternatives still considered likely.

[edit] See also

[edit] References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press. - This article uses text from Volume IV of A Dictionary of Christian Biography, Literature, Sects and Doctrines by William Smith and Henry Wace.

- ^ The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary on Historical Principles (3 ed.), Oxford University Press, 1973, p. 1417

- ^ Rorty, Richard (1979), Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature, Princeton University Press page 38.

- ^ See entry for νόος in Liddell & Scott, on the Perseus Project.

- ^ See entry for intellectus in Lewis & Short, on the Perseus Project.

- ^ This is from I.130, the translation is by A.T. Murray, 1924.

- ^ Long, A.A. (1998), Nous, Routledge, http://www.muslimphilosophy.com/ip/rep/A075.htm

- ^ Metaphysics I.4.984b.

- ^ Kirk; Raven; Schofield (1983), The Presocratic Philosophers (second ed.), Cambridge University Press Chapter X.

- ^ Kirk; Raven; Schofield (1983), The Presocratic Philosophers (second ed.), Cambridge University Press . See pages 204 and 235.

- ^ a b Kirk; Raven; Schofield (1983), The Presocratic Philosophers (second ed.), Cambridge University Press Chapter XII.

- ^ Anaxagoras, DK B 12, trans. by J. Burnet

- ^ So, for example, in the Sankhya philosophy, the faculty of higher intellect (buddhi) is equated with the cosmic principle of differentiation of the world-soul (hiranyagarbha) from the formless and unmanifest Brahman. This outer principle that is equated with buddhi is called mahat (see wikipedia entry on Sankhya)

- ^ The translation quoted is from Amy Bonnette. Xenophon (1994), Memorabilia, Cornell University Press

- ^ On the Perseus Project: 28d

- ^ Kalkavage (2001), "Glossary", Plato's Timaeus, Focus Publishing

- ^ 28c and 30d. Translation by Fowler.

- ^ Fowler translation of the Phaedo as on the Perseus webpage: 97-98.

- ^ Philebus on the Perseus Project: 23b-30e. Translation is by Fowler.

- ^ Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Aristotle's Ethics, Glossary of terms [1]

- ^ "Intelligence (nous) apprehend each definition (horos meaning "boundary"), which cannot be proved by reasoning". Nicomachean Ethics 1142a, Rackham translation.

- ^ Nicomachean Ethics VI.xi.1143a-1143b. Translation by Joe Sachs, p. 114, 2002 Focus publishing. The second last sentence is placed in different places by different modern editors and translators.

- ^ a b c Davidson, Herbert (1992), Alfarabi, Avicenna, and Averroes, on Intellect, Oxford University Press

- ^ De Anima, Bk. III, ch. 5, 430a10-25 translated by Joe Sachs, Aristotle's On the Soul and On Memory and Recollection, Green Lion Books

- ^ See Metaphysics 1072b.

- ^ 1075

- ^ Generation of Animals II.iii.736b.

- ^ a b c d e Menn, Stephen (1998), Descartes and Augustine, University of Cambridge Press

- ^ Lacus Curtius online text: On the Face in the Moon par. 28

- ^ De anima 84, cited in Davidson, page 9, who translated the quoted words.

- ^ a b Davidson p.43

- ^ Davidson page 12.

- ^ Translation and citation by Davidson again, from Themistius' paraphrase of Aristotle's De Anima.

- ^ Davidson page 13.

- ^ Davidson page 14.

- ^ Davidson p.18

- ^ See Moore, Edward, "Plotinus", Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, http://www.iep.utm.edu/plotinus/ and Gerson, Lloyd, "Plotinus", Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/plotinus/ . The direct quote above comes from Moore.

- ^ Encyclopedia of The Study in Philosophy (1969), Vol. 5, article on subject "Nous", article author: G.B. Kerferd

- ^ Iren. Haeres. I. i. 1-5; Hippol. Ref. vi. 29-31; Theod. Haer. Fab. i. 7.

- ^ Iren. I. xxiv. 4; Theod. H. E. i. 4.

- ^ Hipp. vi. 25.

- ^ Clement of Alexandria, Strom. iv. 25.

- ^ Hipp. vi. 12 ff.; Theod. I. i.

- ^ Hipp. vi. 20.

- ^ Ap. Hipp. vi. 18.

- ^ Herodotus, i.

- ^ Davidson pp.12-14. One possible inspiration mentioned in a commentary of Aristotle's De Anima attributed to John Philoponus is a philosopher named Marinus, who was probably a student of Proclus. He in any case designated the active intellect to be angelic or daimonic, rather than the creator itself.

- ^ Davidson p.18 and p.45, which states "Within the translunar region, Aristotle recognized no causal relationship in what we may call the vertical plane; he did not recognize a causality that runs down through the series of incorporeal movers. And in the horizontal plane, that is, from each intelligence to the corresponding sphere, he recognized causality only in respect to motion, not in respect to existence."

- ^ Davidson pp.58-61.

- ^ a b Davidson ch. 4.

- ^ Davidson p.86

- ^ From Shifā': De Anima 45, translation by Davidson p.96.

- ^ Davidson pp.102

- ^ Davidson p.104

- ^ Davidson pp.111-115.

- ^ Davidson p.123.

- ^ Davidson p.356

- ^ Davidson ch.7

- ^ See, for example, the many references to nous and the necessity of its purification in the writings of the Philokalia

- ^ Cross, Frank L. and Livingstone, Elizabeth, ed (2005). "Platonism". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. Oxford Oxfordshire: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192802909.

- ^ TeSelle, Eugene (1970). Augustine the Theologian. London. pp. 347–349. ISBN 0223-97728-4. March 2002 edition: ISBN 1-57910-918-7.

- ^ a b Neptic Monasticism

- ^ "What is the Human Nous?" by John Romanides

- ^ "Before embarking on this study, the reader is asked to absorb a few Greek terms for which there is no English word that would not be imprecise or misleading. Chief among these is NOUS, which refers to the `eye of the heart' and is often translated as mind or intellect. Here we keep the Greek word NOUS throughout. The adjective related to it is NOETIC (noeros)." Orthodox Psychotherapy Section The Knowledge of God according to St. Gregory Palamas by Metropolitan Hierotheos Vlachos published by Birth of Theotokos Monastery,Greece (January 1, 2005) ISBN 978-960-7070-27-2

- ^ The Mystical Theology of the Eastern Church, SVS Press, 1997. (ISBN 0-913836-31-1) James Clarke & Co Ltd, 1991. (ISBN 0-227-67919-9) pgs 200-201

- ^ G.E.H; Sherrard, Philip; Ware, Kallistos (Timothy). The Philokalia, Vol. 4 Pg432 Nous the highest facility in man, through which - provided it is purified - he knows God or the inner essences or principles (q.v.) of created things by means of direct apprehension or spiritual perception. Unlike the dianoia or reason (q.v.), from which it must be carefully distinguished, the intellect does not function by formulating abstract concepts and then arguing on this basis to a conclusion reached through deductive reasoning, but it understands divine truth by means of immediate experience, intuition or 'simple cognition' (the term used by St Isaac the Syrian).The intellect dwells in the 'depths of the soul'; it constitutes the innermost aspect of the heart (St Diadochos, 79, 88: in our translation, vol. i, pp.. 280, 287). The intellect is the organ of contemplation (q.v.), the 'eye of the heart' (Makarian Homilies).

- ^ a b The Mystical Theology of the Eastern Church, by Vladimir Lossky SVS Press, 1997, pg 33 (ISBN 0-913836-31-1). James Clarke & Co Ltd, 1991, pg 71 (ISBN 0-227-67919-9).

- ^ ANTHROPOLOGICAL TURN IN CHRISTIAN THEOLOGY: AN ORTHODOX PERSPECTIVE by Sergey S. Horujy [synergia-isa.ru/english/download/lib/Eng12-ChicLect.doc] [2]

- ^ "THE ILLNESS AND CURE OF THE SOUL" Metropolitan Hierotheos of Nafpaktos

- ^ The Relationship between Prayer and Theology

- ^ "JESUS CHRIST - THE LIFE OF THE WORLD", John S. Romanides

- ^ Metropolitan Hierotheos Vlachos (2005), Orthodox Psychotherapy, Tr. Esther E. Cunningham Williams (Birth of Theotokos Monastery, Greece), ISBN 978-960-7070-27-2

- ^ a b , http://books.google.be/books?id=WHILCw0hDA4C&pg=PA253

- ^ Martinich, Aloysius (1995), A Hobbes Dictionary, Blackwell, p. 305

- ^ Nidditch, Peter, "Foreward", An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, Oxford University Press, p. xxii

- ^ Hobbes, Thomas, "II. Of Imagination", The English Works of Thomas Hobbes, 3 (Leviathan), http://oll.libertyfund.org/?option=com_staticxt&staticfile=show.php%3Ftitle=585&chapter=89820&layout=html&Itemid=27 and also see De Homine X.

- ^ Hume, David, "I.III.VII (footnote) Of the Nature of the Idea Or Belief", A Treatise of Human Nature, http://oll.libertyfund.org/?option=com_staticxt&staticfile=show.php%3Ftitle=342&chapter=55095&layout=html&Itemid=27#lf0213_footnote_nt018

- ^ The Philosophical Works of Descartes Vol. II, 1968, translated by Haldane and Ross, p.190

- ^ The Philosophical Works of Descartes Vol. II, 1968, translated by Haldane and Ross, p.77

- ^ Think Exist on Blaise Pascal. Retrieved 12 Feb. 2009.

[edit] External links